Story by Peter d’Anjou, from Boat Trader

Most boats under 50 feet in length have 12-volt electrical systems. Yet many experienced boaters can’t tell you much about the batteries they have on board, let alone how their batteries and charging systems work. Take my buddy Jeff, for instance. It’s the middle of the season and one of the two 12-volt batteries on his 30-foot sailboat is nearing the end of its life. When I asked Jeff, an engineer by trade and an experienced boater, what kind of battery he was choosing to replace the old one, he blithely said, “Oh, a cheapo X-mart wet cell.” Clearly driven by short-term economics, my friend may not have realized that batteries using the same charging system should be replaced in sets.

Most boats under 50 feet in length have 12-volt electrical systems. Yet many experienced boaters can’t tell you much about the batteries they have on board, let alone how their batteries and charging systems work. Take my buddy Jeff, for instance. It’s the middle of the season and one of the two 12-volt batteries on his 30-foot sailboat is nearing the end of its life. When I asked Jeff, an engineer by trade and an experienced boater, what kind of battery he was choosing to replace the old one, he blithely said, “Oh, a cheapo X-mart wet cell.” Clearly driven by short-term economics, my friend may not have realized that batteries using the same charging system should be replaced in sets.

There’s a lot to know about marine batteries. I’ve written briefly about them before in Lay-up Tips, but now I realize a primer on batteries would be helpful. Modern day conveniences such as laptop computers and cell phones using lithium ion batteries have contributed much to the knowledge and design of batteries since Gaston Plante initially invented the lead-acid battery in 1859. However, marine batteries, especially the wet-cell kind, are still in the relative dark ages of battery design.

A smart multi-step regulator can sense charge, adjust to the batteries’ charging phase, and optimize longevity. A smart regulator with optional temperature sensor sells for $275 at West Marine.

They are purpose-built and their internal structure will reflect their use—starter, deep-cycle, or dual-purpose—as well as their limitations. For instance, a battery designed for starting your engine will typically have more internal plates closer together, providing more surface area to give that higher, one-time discharge required in powering a starter motor, but will not be as good at the long, steady discharge that deep-cycle batteries, with thicker active plates and higher antimony concentrations give. Deep-cycle batteries can be discharged from 50 to 80 percent and recover easily, while starting batteries don’t like to be discharged more than 50%.

Chemical Types:

Marine batteries are available in three chemical types: Flooded, Gel, and Absorbed Glass Mat (AGM). Regardless of chemical type, they’re rated by energy output, generally expressed as ampere hours, and categorized by how many charges (cycles) the battery is likely to withstand in its lifetime. The output and lifespan will typically dictate price. The use, chemical type, and number of batteries best suited to your boat will depend on the kind of boat, how you use it, and your budget.

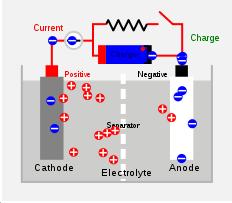

Flooded Batteries: Wet or flooded batteries following Plante’s design are the most common and cheapest kind of battery found on boats. They use a reservoir of liquid sulfuric acid to act as a pathway between lead plates. This electrolyte produces hydrogen and oxygen when the battery is being charged, requiring vented battery boxes and compartments to let the gas escape safely outside the boat. Due to the heat and outgassing produced during charging, flooded batteries require periodic inspection and topping-off with distilled water. They self-discharge at a higher rate (6 to 7% per month) than AGM or gel batteries, and thus require off-season charging. Wet cells must be installed in an upright position (difficult to maintain on boats) and do not tolerate high amounts of vibration (prevalent on boats). The good news is that used batteries are 98% recyclable and flooded batteries handle overcharging better than gel and AGM batteries. Wet-cell batteries are also, as my friend Jeff did know, significantly cheaper than the other types.

Gel Batteries: The “gel” is a combination of sulfuric acid, fumed silica, pure water, and phosphoric acid. The gel is quite viscous and prevents leaks if the battery is inverted or the case is damaged. Charging does cause a small amount of hydrogen and oxygen to be generated at the plates, but the pressure inside the cells combines the gases to create water, so they’re called “recombinant” batteries. This also keeps the battery from drying out due to charging. Gel batteries charge at a lower voltage than flooded or glass-mat batteries, requiring a vessel’s charging system to be very carefully regulated to prevent high voltage overcharging.

AGM Batteries: Absorbed Glass Mat batteries feature glass mat separators saturated with acid electrolyte between the battery’s positive and negative plates. During charging, pressure valves allow oxygen produced on the positive plate to migrate to the negative plate and recombine with the hydrogen, producing water. AGM batteries have better shock and vibration protection than wet or gel batteries, and are virtually maintenance-free.

AGM batteries also have lower internal resistance, allowing greater starting power and charge acceptance, and quicker recharging than other types of deep-cycle batteries. AGM batteries can accept the highest charging current, up to 40% of the amp-hour capacity of the battery, compared to about 25% for the flooded type or 30% for the gel—meaning they recharge faster. Long life, a low 3% self-discharge rate, and outstanding performance make AGM batteries excellent dual-purpose batteries for boaters who require quick starting power and reliable deep-cycle ability. Of course, the price matches the quality.

Boaters don’t realize how much their behavior influences how long a battery lasts. On average, a battery that is properly charged and maintained should last at least three years. What do I mean by properly charged? Marine deep-cycle batteries last the longest and charge the fastest if they’re charged in distinct phases, also called the “Ideal Charge Curve.” Since a battery accepts more current when it’s discharged, the amount of voltage required to “properly” charge a battery differs in each phase depending on temperature. In practice, utilizing a smart charger to regulate voltage in each phase, and recharging the batteries the same day they run down will help you get the most out of your batteries. For more on this I recommend the West Marine Advisor.

Although pricey, I like the AGM batteries for safety and quality reasons—but please don’t install these unless you also install a smart charger. The dual-purpose batteries are a good compromise between the starter and deep-cycle batteries, especially for boats with only one battery used for both starting and for “house” power when the engine is turned off. If you’re not into battery maintenance and proper charging, buy the cheaper batteries as you will inevitably be replacing them sooner than later.

Battery tips

- Stay with one battery chemistry (flooded, gel, or AGM) for all of the batteries on your boat. Each battery type requires specific charging voltages. Mixing battery types can result in under- or overcharging—either of which can be fatal to your battery. A smart multi-step regulator with a temperature sensor to control charge is a wise and safe investment—and a must for AGM or gel batteries.

- Shallow discharges lead to a longer battery life. Given this, it would be foolish not to invest in a solar power trickle charger with smart regulator.

- 80% discharge is the maximum safe discharge for deep-cycle batteries.

- Don’t leave batteries deeply discharged for any length of time. Leaving batteries in a discharged state will cause sulfide damage and lower their capacity.

- Charge batteries after each period of use.

- Never mix old batteries with new ones on the same charging system. Old batteries tend to pull down the new ones in the battery bank to their deteriorated level.

- Keep batteries in acid-proof storage boxes secured with tie downs.

- Clean terminal connectors regularly to avoid loss of conductivity.

- Maintain fluid levels in wet-cell batteries.

- If you have true deep-cycle needs, consider golf cart or traction propulsion batteries.