Story by Kimball Livingston from his always interesting blog, Blue Planet Times …

If you need for me to tell you that Magnus Danbolt’s photograph was taken in tropical waters, not in Northern California, you are perhaps not qualified to read on.

In this space I have celebrated anything and everything driving the technological future of setting forth upon the water. Now is the moment to appreciate a few unique efforts to preserve the heart and spirit of what went before, and what we hope will be a future for the waterways calling us to set forth upon the water, forever and forever.

Finishing the 2011 Transpacific Yacht Race from Los Angeles to Honolulu, more people than ever arrived in Honolulu on their high-tech raceboats talking about trash polluting the Pacific Ocean . . .

And now approaching the mainland are six Polynesian sailing canoes, vaca moanas, arriving from the far reaches of the Pacific with the message: “If we don’t pay attention to the needs of the ocean, we won’t survive as humans.”

The vacas bring a simple message, as important long-term as a debt ceiling agreement in Washington. More so. The unanimity of alarm among evidence-based ocean scientists should alarm even the industry flaks who serve up allegedly-balancing counter views to misguided reporters.Funded by the Okeanos Foundation, the Pacific Voyage began with the departure of the first canoe from Aotearoa, New Zealand in April and has proceeded from one island group to the next. The most recent departure point was Hawai’i. From the web site at Pacific Voyagers I copy:

The canoes are built following a traditional model. Apart from the hull, which is made of fiberglass to protect the environment from tree loss, we used traditional materials. The vaka are very simple, with no running water or fossil fuel-burning engines, apart from natural gas, which is used for cooking only. The traditional design and materials of the vaka are combined with a modern technology: with the energy of the sun we drive solar-powered engines. Whereas the ancestors were using wind to power their movement, we are using wind and sun. In this way, we have merged the best of two worlds – a symbol for how we could bring ancient and modern knowledge together to travel safely into the future.

The ethic is, “To not disturb Tangaroa, the God of the Sea. Move your paddle silently through the sea.”

Photo courtesy Gaualofa/Pacific Voyagers

Coming in from Kauai, after leading the group into the shelter of Drakes Bay and with others stalled at sea for lack of wind, the word from Marumaru Atua (Cook Islands) was all about cold, cold, cold. The crew may or may not have left Kauai aware of the saying, which applies broadly along the Northern California coastline, where south-flowing currents draw up water from the depths, “I spent the coldest winter of my life one summer in San Francisco.”

Arrival in San Francisco Bay was rescheduled from Saturday to Sunday to (let’s hope) Monday. As of Sunday afternoon, two canoes were sheltering in Drakes Bay and four were drifting that direction with little breeze and slow progress. Tentative arrival now is 5 pm Monday. The fleet’s progress can be monitored via Facebook (search Pacific Voyagers) or via AIS at MarineTraffic.com. The group at sea reported sighting a young fin whale trailing castoff fishing gear and a synthetic rope (won’t go away). And so it goes—

The canoes are scheduled to be in San Francisco Bay, at Treasure Island, until an August 8 departure for Monterey, then Santa Barbara, Catalina, LA, and San Diego for a long stopover there, followed by a voyage south as far as the Galapagos, and back into the South Pacific. A public opportunity is offered from 1000 to 1600 on August 6 to meet and greet the crews at Treasure Island.

RECALLING THE RULE OF TULE

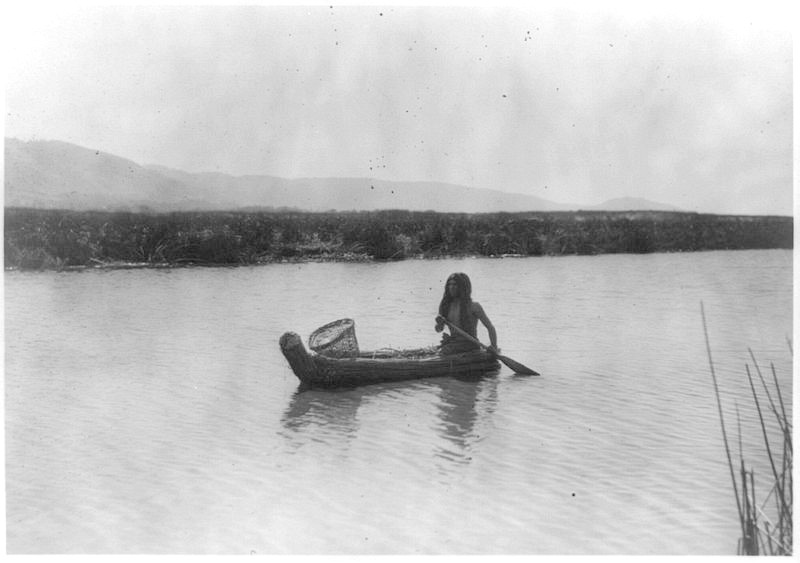

There was a time in Northern California when every tribe had its tule craft, whether they were Miwok, Ohlone or Pomo. Today, only the Clear Lake Band of the Pomo continue to create woven tule boats, and as I understand it, they almost lost it.

Historic photo courtesy Big-Valley.net

As in, It, the memory of how.

The tule boat, woven from tule reeds, was the human ticket to the lakes and rivers of Northern California, and to San Francisco Bay itself. More recently, the Clear Lake Band realized that the art and craft of weaving tule was about to die out, but rather than let that happen, nine years ago they created the annual Tule Boat Festival, a three-day event in which tule is harvested on day one, woven into boats on day two and raced on day three.

In theory.

In practice, there is still a lot of building going on, in the hours before the races on day three.

And, sadly, they don’t harvest where granddaddy harvested, because that shoreline is now polluted with the floridone that the State of California once assured all and sundry would never show up in the plant that, traditionally, served the Pomo as a source of food, shelter, and clothing. But there still are healthy tules to be found, and when I asked, the Clear Lake Band freely invited my family and me to join them for their Tule Boat Festival. They don’t sell tickets. It’s not a media event. It’s not a “public” event, either. You’re either there or you’re not, and I was told but lost track of how many hundreds of pounds of tri-tip hit the barbeque.

I do remember they invited Her Daughtership to jump in and race a canoe.

And I remember that the vibe was mostly about the kids, and at that level it wasn’t so very different from any BBQ, anywhere. It was summertime in America. But there was a theme, and the theme was restoration of a viable population of a fish, the Clear Lake Hitch, that once was part of the basic sustenance for Pomos living on the shores of Clear Lake. And now is not.

Put it this way:

The hitch, an ancient fish endemic to Clear Lake, live in deep in water most of the time, but every spring the adults work their way up the tributary creeks to spawn. In the words of biologist Rick Macedo, they used to “mass by the thousands,” in an annual ritual “as spectacular as any salmon run on the Pacific coast . . . The tumultuous splashing . . . and the appearance of herons, osprey, egrets, and bald eagles . . . signify that the hitch are in.” In recent years the population has declined precipitously, for reasons that are poorly understood. Streambed obstructions, predation by introduced fish, and food competition all have been suggested as possible causes for their diminished numbers. Source: UC Davis California fish web site.

The hitch once ran in every stream, every creek in the region. Now they are down to two streams.

As to boat-building technique, tules are first bound into bundles. The bundles are then re-bound and shaped into boats.

The tule boats of old would be hauled out and dried between uses and would last through a summer season, to be replaced the following year. The boats I saw being assembled and raced were intended for the weekend, and fun for all whether ashore in the gallery . . .

Or in the hunt . . .

Rather often, after an attempt at paddling, the skippers went freestyle . . .

So yes, it was about tradition, and caring for the world about us.

And it was about family, and in the moment

(did I mention, and I wish you a good one)

it was about summer in America . . .

.

Tule Festival photos copyright Kimball Livingston

.